Confessions of a Brain Surgeon review – life-changingly exquisite television

Early on in Confessions of a Brain Surgeon, a crew member pipes up from behind the camera. Would Henry Marsh mind saying something, anything, to see if the microphones are working? “When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” Marsh says instantly, not pausing for a moment to gather the words, “I all alone beweep my outcast state, and trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, and look upon myself and curse my fate.” A simple “testing testing, one two” would be standard practice, but Marsh is not your standard documentary subject.

Marsh is a retired neurosurgeon, having spent decades at the top of his profession. You’ve probably seen hospital documentaries that have featured an “awake craniotomy”, the macabre procedure that keeps a patient with a sawn-open skull conscious, so the effect of the scalpel’s cuts can be monitored in real time. Marsh, along with his longterm colleague, anaesthetist Judith Dinsmore, pioneered that. He performed numerous other exceptionally advanced operations with unique skill. Countless patients who were told by less able, less imaginative medics that they were terminally ill were treated successfully by Marsh.

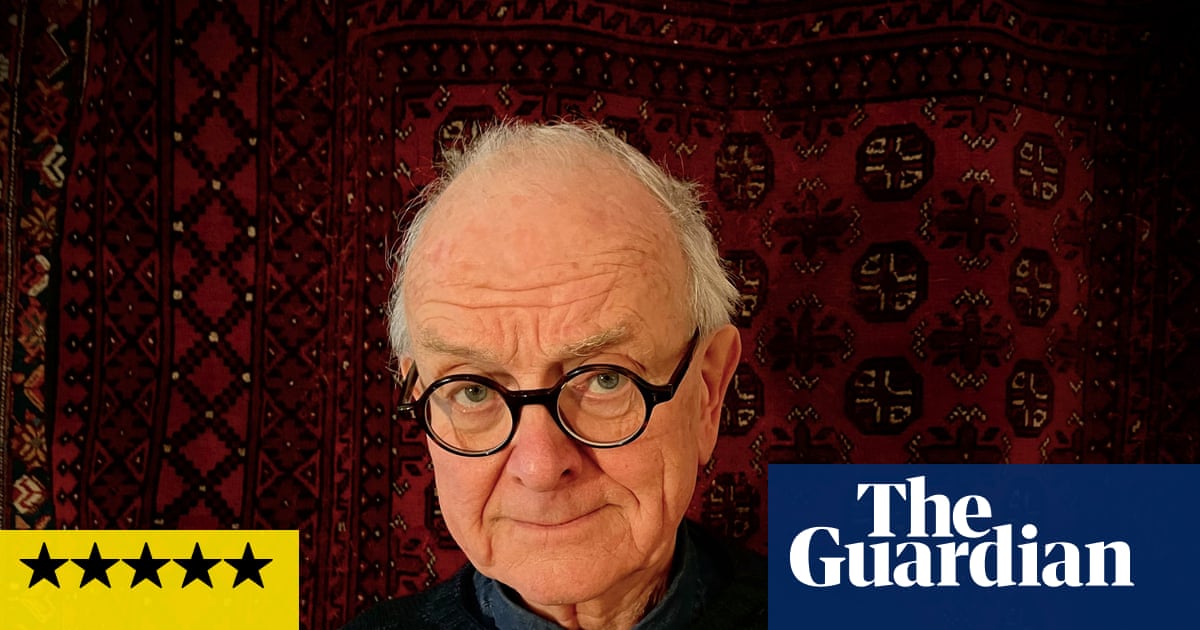

At 75, Marsh is physically and mentally agile, but his own diagnosis of prostate cancer has caused him to reflect. In Charlie Russell and Harriet Bird’s exquisite film, he reviews diaries and home movie footage, and meets important people from his past.

So how does this man, the one with Shakespeare sonnets ready on his tongue, feel to have been the best at the vocation we use as shorthand for the world’s hardest job? “All surgeons carry inside themselves an inner cemetery,” he says. “A place full of bitterness and regret.” Every professional lifesaver is haunted by the people they were unable to help, but Marsh is so troubled by the relatively few patients who died on his table that he can’t take pleasure in his many successes. He struggles even to remember them.

Confessions of a Brain Surgeon is his quest to rectify that, and make peace with himself. The result, powered by Marsh’s pitiless acuity and disarming eccentricity, is a deep meditation on what it means to have lived: death hands us a ledger of triumphs and mistakes, the happiness we’ve spread tallied against the pain we’ve inflicted. Was it all worth it?

Marsh remembers a 16-year-old girl who had a life-altering stroke after her operation. He remembers patients who did not survive at all. Reviewing his trips to Ukraine, which he has visited regularly as a volunteer since 1992, he finds footage of Tania, a girl he brought back to London but could not cure. “I look at this with complete horror,” he says, peering through the thick, round spectacles that enhance his hawkish gaze. “Horror” is the word he uses most often.

With the help of his first wife, Hilary, Marsh also looks back at the negative effect his calling had on his personal life. Was he a workaholic who sacrificed his family’s happiness to drive himself forward? Yes, but as with seemingly everything in Marsh’s life, matters had a cruelly precise balance and inevitability to them. He chose to train as a neurosurgeon after his first child, William, became seriously ill at the age of three months. The baby recovered after a successful brain operation but the ordeal was, Marsh says, “horror beyond horror”.

An already piercingly emotional documentary shifts up a gear during Marsh’s meeting with a woman named Tina. Almost thirty years ago, Tina’s four-year-old son Max had a brain tumour, and Marsh said he could fix it. He was wrong. In a stunningly frank exchange, Tina admits that she has carried a hatred for Marsh ever since Max died; Marsh admits that he misdiagnosed the type of tumour Max had “because I was arrogant”. But then Tina lets go and forgives, for the simple reason that Marsh has full recall of the case: he remembered her little Max. Suddenly this brusque scientist leans across the table and grasps both Tina’s trembling hands. “Of course I remembered.”

Further redemption comes from reunions with Dinsmore, the anaesthetist, who reminds Marsh of the great work they did; and his long-serving secretary Gail, who says it was an honour to assist him. Then there is an old patient, Jude, who was a new mum in 2002 when she was told by doctors that her tumour was inoperable. Marsh disagreed; Jude recently saw her son graduate. In her house, Marsh is shown a wall of family photos, each memory a gift bestowed by the dedication that has brought him unimaginable anguish. Was it all worth it? The film ends with Marsh still weighing the evidence, but we’re given reason to hope that his answer will be yes.

Confessions of a Brain Surgeon aired on BBC Two and is on iPlayer now